text #1

The oldest light we can observe, the cosmic microwave background radiation, is nearly 14 billion years old. One of the defining traits of light is that it cannot truly be owned, at least not yet.

A line can be said to span two ends of a spectrum of light: sunlight, the natural and warm light that is about 8 minutes and 19 seconds old when it reaches Earth, and light from distant stars that has traveled for thousands of years, on the one hand, to light from artificial sources or reflected light, on the other hand, that reaches us in nanoseconds.

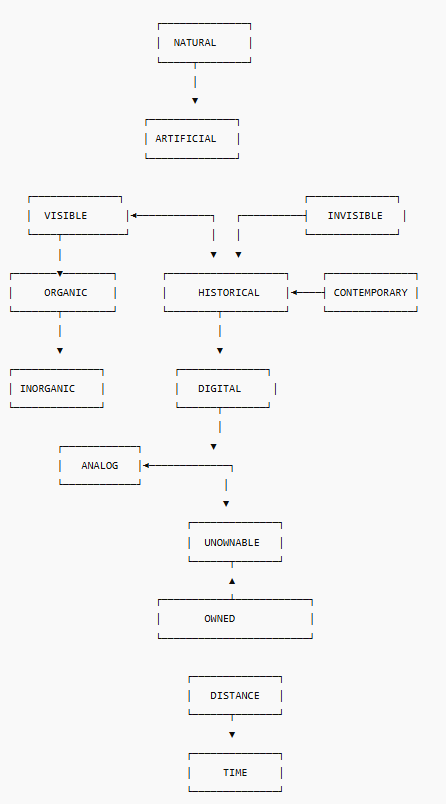

So we see one axis representing the distance light travels, so to speak, and another axis covering the range from natural to artificial light.

The word “artificial” is interesting in this context because, like light itself, the word comes to us whether we want it or not. It originates from the Latin artificialis, which in turn traces back, just as light moves outward, to artificium.

From this we get the root ars, meaning art or skill (derived from facere, to make, create, or bring forth).

Lead white is produced by exposing lead plates to vinegar fumes and carbon dioxide. This process forms a white crust on the lead, which is then scraped off and used as pigment. Around 1840, zinc white was invented, and titanium white followed in 1919.

These pigments, in contrast to the ochre, hematite, manganese oxide and charcoal that was used in ancient cave paintings, like Derrida’s concept of the pharmakon, are artificial and human-made.

The production of pigments transforms substances from something natural into something new and artificial. They are toxic, potentially lethal, yet also represent a form of technology that enables new kinds of art.

“People can often be heard exclaiming, “Look at that natural light,” even while standing in artificially lit museum rooms.

ALSO SEE:

Open Call: The Art of Artificial Intelligence | The Wrong Biennale 2025/2026

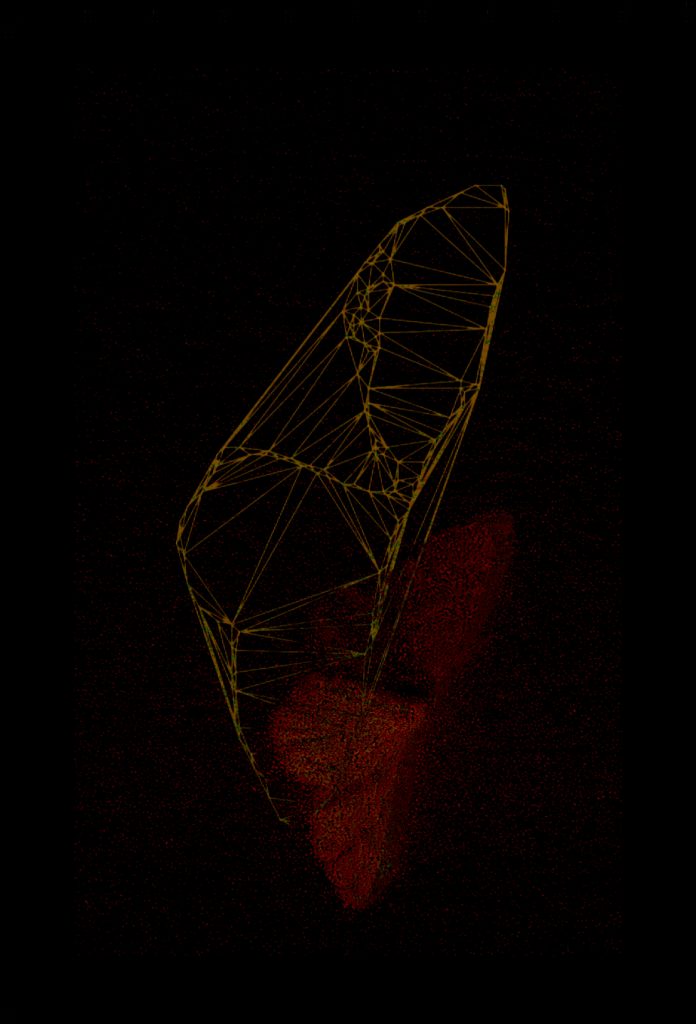

object #1 – fragment of degas

The original painting is currently on view at Glyptoteket in Copenhagen as part of the exhibition Degas’ Obsession, running through November 29.

Object 1 reveals a geological-like structure. It is a very small fragment taken from the painting by Edgar Degas. It is a very small fragment taken from the painting by Degas, painted around 1882, and photographed through a Zeiss microscope (a process that uses artificial light) using a method called X-ray fluorescence (etymologically derived from the mineral ‘fluorspar’) spectroscopy (XRF).

So we have the literal (the title of the painting, the painter’s name), the mineral (the pigments), and the artificial (the creation of a representation of a scene that did not exist in a single point of time, but was the result of years of editing).

The fragment was then photographed again with a camera using a CCD sensor, which offered a new perspective on the light. The combination of the microscope, camera lens, and CCD sensor created an image of something that Degas himself never saw as a visible object; yet, through this process, it was transformed into an object in its own right.

The artificial light that Degas used, whether from gas lamps or early electric sources, enabled the creation of a toxic pigment due to its lead content.

More recent research has shown that it is possible to stop light by deforming the structure of two-dimensional photonic crystals. This could pave the way for quantum computers and groundbreaking methods of data storage.

The second object is digital and inorganic from beginning to end, offered as both a reference point and a contrast to the tiny paint flake from Degas’s Dancers Practicing in the Foyer.

The Getty Conservation Institute has described the method in connection with a similar analysis being done on the ‘The Milliners’ after an X-ray had shown several phases of rework (including erasing and adding persons):

“Because XRF is an X-ray technique, information is gathered simultaneously from all the paint layers; therefore, elements may be detected from a ground layer, together with those from overlying paint layers. If the painting has a complicated layer structure (as the X-radiograph indicates is likely the case for The Milliners), it is usually necessary to remove small samples for additional analysis in order to more fully understand the painting’s construction.

Samples taken from paintings are barely visible to the human eye (their size is less than 1 mm, typically on the order of only several hundred microns). Working under a microscope and in collaboration with a conservator, the scientist will take samples using fine surgical tools. Sometimes merely a scraping is required, but more frequently samples of all the paint layers are taken and mounted to reveal a cross-section of the painting’s stratigraphy. An ideal cross-section sample will contain all the layers of a painting from the ground layer to the final varnish.”

“From elemental analysis of the individual layers, it was determined that the ground layer is composed of lead white and barytes; the dark layer above it of lead white, bone black, and barytes, while the bright red particles are vermilion. The light brown layer towards the right of the sample is lead white and iron oxide earths (red ochre by visual examination), with associated minerals. The bright central layer is red lead followed by a lead white layer with chrome green and red ochre particles throughout. The thin dark layer at the top is lead white with iron oxide earths (again, red ochre by visual examination)”

— The Working Methods of Degas: The Milliners, The Getty Conservation Institute, 2008

Based on similar technical analyses, researchers could establish that Degas started working on ‘Dancers in the foyer’ a lot earlier than previously though – and that he worked on it, adding and removing layers and motifs, for close to 30 years. The paiting contains up to 14 layers of paint.

Interestingly, a painter often praised for his instinctive ability to capture a fleeting moment in motion may have spent up to 30 years doing just that, and that material traces of this long process are chronologically embedded, almost written or woven into the very structure of the painting, traces that were previously invisible and therefore beyond our understanding.

object #2

X / TBA

diagram #1